DirectX 10.1

In the first half of 2008, Microsoft is expected to roll out the first service pack for Windows Vista and one part of this update will be DirectX 10.1. Because of the way DirectX evolved with DirectX 10, there are no longer any optional features (otherwise known as cap bits). This means that, in order to obtain support for the API, the hardware has to support every feature in the API – this ethos hasn’t changed with DirectX 10.1.AMD’s ATI Radeon HD 3800-series products are the first to support the new API and, because none Nvidia’s current hardware is fully DX10.1 compliant, it’s something that the company is playing down. We’re back in a similar situation to the one we had with the GeForce 6800 and the Radeon X800, where the former supported Shader Model 3.0 (DirectX 9.0c) and the latter only supported Shader Model 2.0 (DirectX 9.0).

ATI played down Shader Model 3.0 pretty heavily by claiming that Nvidia’s hardware couldn’t realistically use some of the benefits of SM3 because of a poor implementation. The company also claimed that the increased instruction lengths didn’t mean anything, as very comparable image quality could be achieved using Shader Model 2.0b extensions. Subsequently, it came as no surprise that when ATI launched its first Shader Model 3.0 parts, it hailed the design as “Shader Model 3.0 done right”.

Despite ATI’s downplaying of SM3.0 when it didn’t have hardware, we’re in a situation now where games are coming out that simply don’t have a Shader Model 2.0 fallback, with Shader Model 3.0 being the minimum required in some cases. It’s an unfortunate situation, because there are a lot of gamers out there with perfectly good SM2.0 hardware that cannot play some of the latest games.

This was one worry we had with DirectX 10.1, but having spoken to AMD, Microsoft, Nvidia and a number of developers, all have gone on record with us to say that DirectX 10.1 is never going to become a minimum specification – it’s merely a series of extensions to DirectX 10.0. The reason why DirectX 10.1 is turning up is that there were some parts of DirectX 10.0 that had to be omitted because neither hardware vendor was ready to implement the features in the timeframe for their release schedules.

Given the fact that DirectX 10.0 (and 10.1 for that matter) hardware is either compliant or not, Microsoft had to delay some of the features developers wanted to include in the API. As a result, Microsoft refers to DirectX 10.1 as ‘Complete D3D10’, because it includes all of the features it set out to include from day one.

If you go back to our interview with Nvidia’s Roy Taylor, he mentioned that game publishers really care about installed bases. Think about that for a second. There’s a lot of DirectX 10.0 hardware out there and it would be bad business for game publishers to turn away from that userbase, even if the developers wanted to. As a matter of personal opinion, I don’t think we’re going to see games with a DirectX 10.0 minimum specification until early 2009; at least, that’s what everything I’ve seen and heard points to.

Obviously, this is good news for anyone that owns a card from either the GeForce 8-series or the Radeon HD 2000-series, as your cards aren’t going to become obsolete overnight, but that’s not to say that there aren’t some benefits to DirectX 10.1.

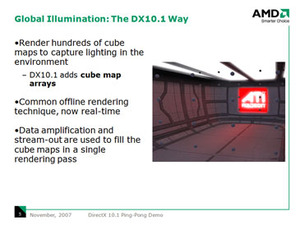

Indexable Cube Map Arrays:

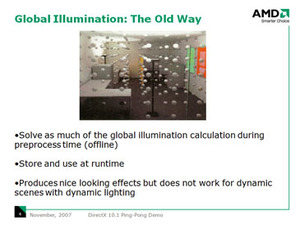

The biggest benefit that AMD has been pushing is a technique called Global Illumination – this isn’t a new technique and you will have seen the effect used to some extent in older titles, but what DirectX 10.1 does is make this a real-time effect. In the past, it was an effect that was too inefficient to implement effectively and most of the calculations were done before the pixels were processed.How DX10.1 makes this a real-time effect is thanks to indexable cube map arrays. The best way to imagine this is if you break a scene down into small cubes and each cube has a small sphere in its centre. The cube map allows you to calculate how light will interact with objects in that space by creating a three-dimensional texture coordinate that specifies the orientation of the light from the sphere in the centre of the cube map.

Now if you multiply this to fill an entire scene, there’s a lot of cube maps that need to be calculated if you’re going to create a realistic-looking scene. DirectX 10.1 allows you to read and write to multiple cube maps in a single rendering pass – this makes the whole process many times more efficient and, as a result, enables real-time global illumination.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.